Imagine you’re sick—burning up with a fever. You know your body is fighting something. So, what do you do? Rest, maybe grab some meds, and wait it out. But if you’re a frog? You crawl onto a sunny rock and literally heat yourself up.

Yes, really.

Cold-blooded animals, or ectotherms, have a fascinating trick up their evolutionary sleeves. They can’t regulate their body temperature internally like we do, so when they’re sick, they regulate it externally.

And here’s the kicker: it actually works.

Cold-blooded ≠ defenseless: What you never learned in biology class

For a long time, scientists assumed reptiles, amphibians, and fish had weak, primitive immune systems. They do, in a sense, rely on similar defense structures as mammals, but their tools work a little differently, and sometimes more creatively.

Cold-blooded vertebrates rely on both:

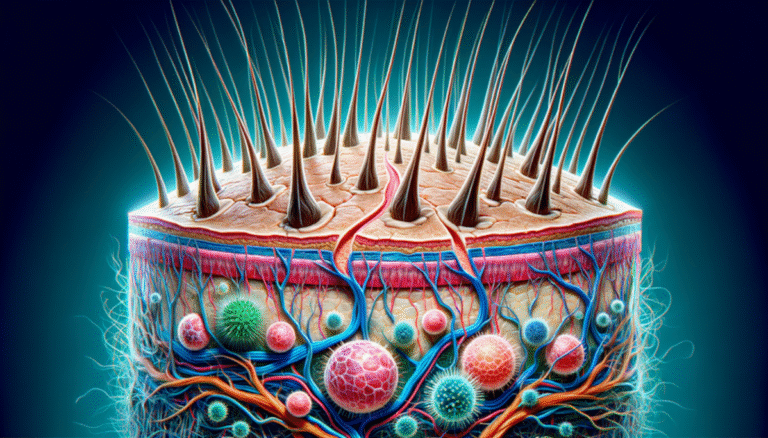

- Innate immunity: Think of this as the “emergency responders”—skin as a physical barrier, immune cells like macrophages and granulocytes rushing in, and the complement system triggering inflammation and cell clean-up.

- Adaptive immunity: This involves the specialized forces—T cells and B cells. They recognize specific pathogens and even create “memories” to fight them faster next time. Amphibians and reptiles even make antibodies like IgM and IgY (yes, that’s a thing).

So far, so familiar. But here’s where things get wild.

When fever isn’t just a symptom—it’s a strategy

Cold-blooded animals don’t get a biologically induced fever like humans. Instead, they engage in behavioral fever—actively seeking warmer temperatures when infected.

In a groundbreaking 1998 experiment by Kluger et al., lizards infected with bacteria were offered a temperature gradient. Infected animals moved to warmer zones, while healthy ones stayed cool. The warm-seekers cleared their infections faster and lived longer. Nature’s sauna therapy, if you will.

But how does warmth actually help?

Case study: Nile tilapia vs. viral infection

In 2024, researchers observed that Nile tilapia—an important aquaculture species—ramped up their immune system when allowed to induce fever behaviorally. Key outcomes included:

- Reduced T cell apoptosis: Fewer immune cells died prematurely.

- Increased production of interferon-gamma and granzyme B: These are immune weapons that help “shoot and shred” infected cells.

- Overall increased cytotoxicity: A clear, measurable boost in the fish’s ability to eliminate viral threats.

In essence, behavioral fever doesn’t just make these animals feel better—it optimizes their immune system’s entire infrastructure.

The ancient roots of immunity

What behavioral fever shows us is simple but profound: cold-blooded animals aren’t limited by their physiology. Instead, they’ve evolved clever behavioral strategies to accomplish what warm-blooded animals have internalized. It’s not just about hot blood—it’s about resourcefulness.

As early vertebrates, amphibians and reptiles may have pioneered some of the first truly adaptive immune systems on Earth, laying the groundwork for the complex responses you and I experience today.

Even crazier? Their behavioral choices (like basking in the sun) might be distant ancestors to your own instincts, like reaching for a warm blanket when you’re unwell.

Final takeaway

Cold-blooded animals might not have a thermostat built in, but they’ve hacked biology to survive—and sometimes even thrive—during infection.

So next time you see a turtle sunbathing, know this: it’s not just relaxing. It might be fighting for its life in one of the most ancient and effective ways nature ever invented.

Leave a Comment