When most people hear “Ice Age,” they picture a frozen world where mammoths and saber-toothed cats roamed before vanishing into extinction. It’s easy to assume that such intense cold must have wiped out nearly everything in its path—another mass extinction event like the one that killed the dinosaurs.

But here’s the wild truth: The Ice Ages didn’t break life—they built its resilience.

Wait… there wasn’t a mass extinction?

Despite glaciers covering up to 30% of Earth’s surface at their peak, the Ice Ages didn’t bring about a global mass extinction like the “Big Five” extinction events you may have heard of. Instead of wiping species off the map entirely, these icy chapters caused patchy, regional waves of extinction and shook ecosystems in unpredictable ways.

In the most recent one—the Pleistocene Ice Age, which ended about 11,700 years ago—we did lose some truly incredible megafauna. Think:

- Mammoths

- Woolly rhinos

- Saber-toothed cats

- Giant ground sloths

Roughly 35 species of large mammals vanished in North America alone. But compared to mass extinctions like the Permian event (which wiped out over 90% of marine species), this wasn’t even in the same league.

What stopped the Ice Age from becoming mass extinction #6?

The real secret: life moves fast—and smart

Turns out, most life survives by doing what it’s always done: adapt, move, or die. And many species chose the first two options:

- Cold-loving species expanded across frozen tundras.

- Warm-adapted animals and plants retreated to ice-free “refugia”—isolated pockets where conditions stayed mild enough to survive.

- Some adapted over time. Others, unfortunately, couldn’t and disappeared.

For example, evidence from pollen analysis in ice cores shows how forests shifted southward during glacial periods—literally rolling with the punches. In Europe, many species survived in the warmer Mediterranean basin. In North America, biodiversity clung to areas like southern Florida or the unglaciated pockets of the Rockies.

Flashback: When an ice age brought mass extinction

But not every glaciation was so gentle. During the Late Ordovician glaciation (~444 million years ago), global cooling and a sharp drop in sea levels triggered Earth’s second-deadliest mass extinction event. Up to 85% of marine species vanished as shallow seas dried up and ecosystems collapsed.

The difference? Timing. The biosphere back then was dominated by marine life, and it didn’t yet have the toolkits of mobility or environmental diversity found in later eras.

After the storm: How ecosystems came roaring back

Here’s the part that blows scientists away: once the glaciers retreated, life didn’t just recover—it exploded.

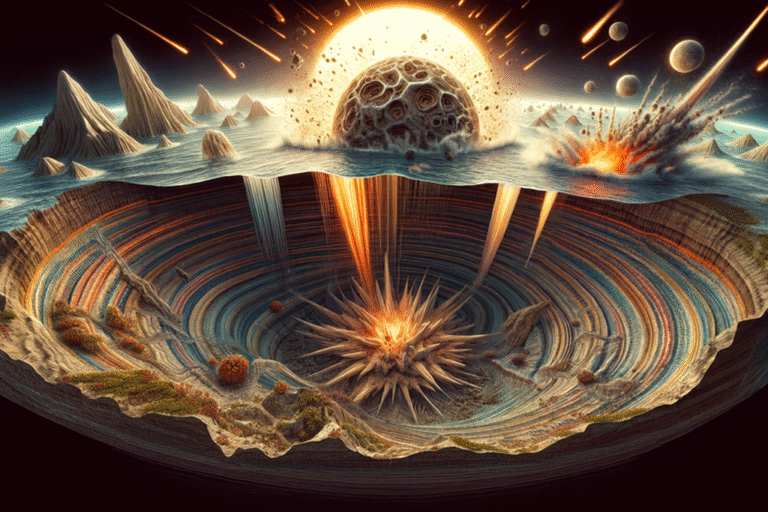

Just imagine: mile-thick walls of ice begin to melt. Rivers form. Valleys reemerge. New soil, carved by glaciers, sits untouched and nutrient-rich. It’s a fresh start.

Into that empty canvas rush in hardy plants and animals. We’ve seen this happen in real time, too—like how life quickly returned to areas under modern ice sheets or even volcanic destruction, such as Mount St. Helens.

Fossil records and genetic studies show that ecosystems post-Ice Age diversified rapidly due to:

- New ecological niches

- Rising CO₂ levels are fueling plant growth

- Warmer, wetter climates are spreading biodiversity

After the Ordovician extinction, for example, land plants seized the opportunity to expand dramatically. Before the cooling event, land life was minimal. Afterward? The green invasion began—and never stopped.

What this means for us today

The story of the Ice Ages isn’t just about the survival of the mammoth or the downfall of the saber-tooth. It’s a story of life’s grit. Its ability to pivot, evolve, and sometimes, just hunker down and wait.

That should stir something in you. Because while environmental shifts today are faster and more human-driven than Ice Ages of the past, the instincts of adaptation and resilience still echo in every species—us included.

So here’s the question: what refugia are you building? What shifting climates—literal or metaphorical—are shaping your world right now?

History shows that those who move, adapt, or dig in typically live to write the next chapter.

Leave a Comment