If you’ve ever wondered when the Earth’s carbon problem really began, you’re not alone. It’s easy to assume that carbon levels in our atmosphere have gone up simply because “there’s more of it” now. But what if I told you that the total amount of carbon on Earth hasn’t actually changed in millions of years? That it not about having more carbon, but about where that carbon is stored?

This twist in the carbon story changes everything—and it starts deep underground.

The Earth isn’t adding carbon—it’s just reshuffling it

Let’s start with a fundamental truth: Earth is a closed system for carbon.

That means we don’t gain or lose measurable amounts of carbon from space. The total amount of carbon has stayed essentially the same over geological time. But what has changed—dramatically—is how that carbon is distributed between Earth’s atmosphere, oceans, living organisms, and underground rock layers.

Once upon a time, more carbon was on the move

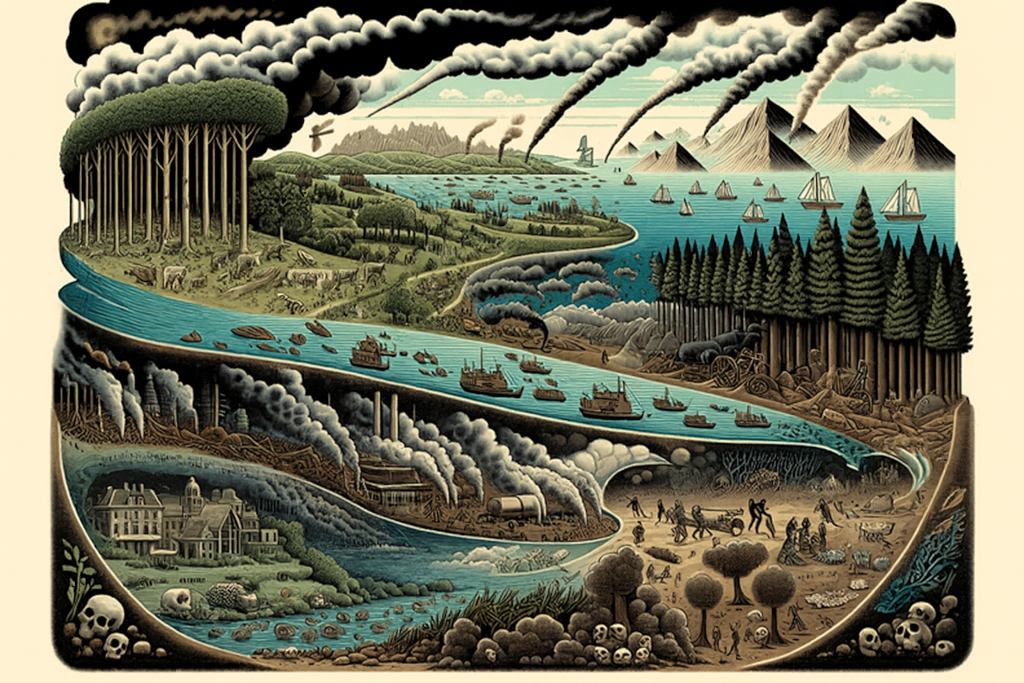

Millions of years ago, Earth’s carbon cycle was buzzing with activity. Carbon was constantly cycling between the air, oceans, plants, animals, and microbes. This is what scientists call the “active carbon cycle”.

During that time, carbon wasn’t hiding beneath the planet—it was floating through forests, rivers, and clouds. Then something fascinating happened: life figured out how to store carbon.

Fossil fuels: nature’s long-term storage plan

Over time, dead plants and microscopic marine life were buried under layers of sediment. Over millions of years, pressure and heat transformed this organic matter into coal, oil, and natural gas—what we call fossil fuels.

This process effectively “locked away” massive amounts of carbon underground, taking them out of the short-term carbon cycle. It was carbon’s version of going into hibernation.

It’s been like that for eons. But what changed? We did.

How humans woke up Earth’s dormant carbon

In the last 150 years—thanks to the Industrial Revolution—we’ve dug up more than just coal and oil. We’ve unleashed that stored carbon back into the atmosphere faster than nature can rebalance.

Burning fossil fuels adds carbon dioxide (CO₂) into the atmosphere, turning ancient carbon into a modern problem. The rate of this return is astonishing:

- A NOAA study found that humans release over 36 billion tons of CO₂ into the air each year.

- Ice core records show that CO₂ levels have shot from 280 parts per million (ppm) in pre-industrial times to over 420 ppm in just a century.

It’s not that there’s more carbon now—it’s that carbon that used to be safely underground is back in the game, and tipping the balance.

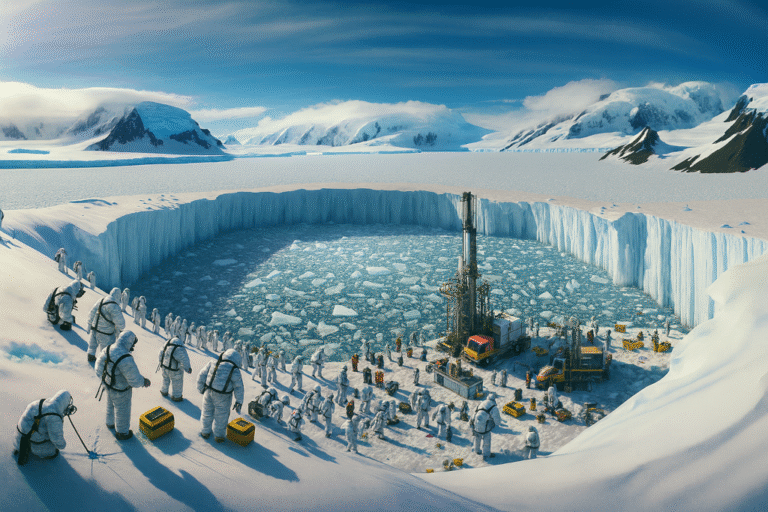

The evidence is locked—and melting—in the Earth

One of the clearest experiments showing ancient carbon’s reentry comes from Arctic permafrost research. As permafrost melts, scientists are finding the remains of carbon-rich plant matter previously frozen for tens of thousands of years—now thawing and emitting CO₂.

Similarly, deep-sea sediment cores reveal layers of organic carbon from different geological eras, showing that significant portions of carbon were once part of life above ground—until buried.

The takeaway: carbon isn’t new—it’s just out of place

So, was there more carbon in the carbon cycle before fossil fuels formed? Not more carbon total—but far more “available” carbon actively moving through ecosystems.

By unlocking fossil fuels, we’ve rapidly reintroduced ancient carbon into this active cycle—carbon that the planet had slowly and wisely tucked away.

Now that we understand this, the question isn’t whether Earth has too much carbon. It’s where that carbon is—and what we choose to do with it next.

Want to keep diving into Earth’s incredible systems? Explore how ocean currents work like Earth’s thermostat or why trees are climate superheroes. The more we understand, the smarter we act.

Leave a Comment